One of the questions that inevitably arises after a school shooting is:

When the shooter clearly showed signs of trouble, why wasn’t the attack prevented?

“Prevention is the missing piece after every attack,” Attorney General Dave Yost said. “And the safety of children across our state depends on us plugging that gap.”

To that end, Yost and his team of school-safety experts have devised an initiative centered on the prevention of targeted violence. It will send funding to both law enforcement officers and schools.

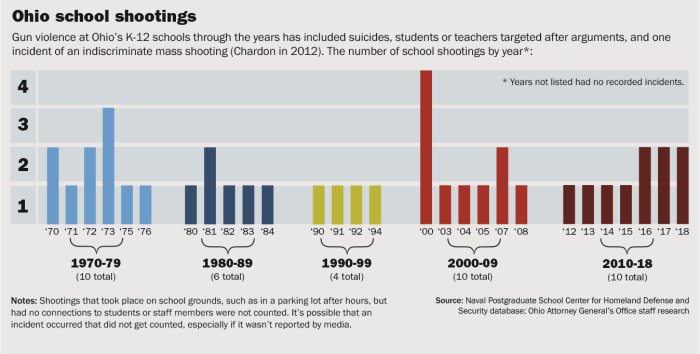

“Since a teen gunman killed three students at Chardon High School in 2012, Ohio has started a tip line and worked with schools to create emergency plans,” the attorney general said. “Those are like bookends on a shelf, and what we still need are the books, which give meaning to the space in between.

“That’s why we’re asking law enforcement officers and school officials to team up to help prevent violence.”

Such teamwork is essential, said John Hartman, a school resource officer with the Delaware City Police and vice president of the Ohio School Resource Officers Association.

“The overall safety of any school building is dependent on everyone,” said Hartman, who consulted on the initiative. “It is not just law enforcement. It’s teachers, administrators, students, parents and officers all working together to be aware and involved.”

That is why the AG’s plan calls for the creation of multidisciplinary teams to evaluate threats or any concerning behaviors to determine whether they pose a risk.

The teams would focus on getting help for the student (or other individual) whose behavior is concerning, ideally well before the person thinks about planning an attack, said Mark Porter, who, as a former U.S. intelligence official and Yost’s director of law enforcement operations, helped craft the initiative.

Said Hartman: “The key is having the training and resources in place beforehand, so threats can be identified and the proper individuals can receive intervention prior to acting.”

The program works hand-in-hand with training provided to schools and students by the Ohio Department of Education and the nonprofit Sandy Hook Promise, created after a gunman killed 20 schoolchildren in Connecticut in 2012.

“I don’t think anyone believes you’re going to prevent every bad thing in the world from happening,” said John Born, a former Ohio public safety director and former superintendent of the State Highway Patrol, who also served as a consultant on the new initiative.

“But you can prevent many bad things from happening,” he said. “And that’s why, when fully implemented, this will be the most significant thing we’ve done in Ohio to prevent potential violence in schools.”

How the initiative works

The initiative has two segments, said Porter, who previously led the U.S. Secret Service’s Protective Intelligence and Assessment Division, which includes the National Threat Assessment Center.

In the first segment, every school district will be encouraged to create one or multiple Behavioral Assessment Teams, safety-minded groups that some Ohio districts, including Dublin City Schools and South-Western Schools, already are experimenting with. House Bill 123, introduced this year and still pending, would make the teams mandatory for schools with grades 6-12.

These teams, consisting of five to eight members (including the school superintendent or a designee and a police officer), will deal with reports of concerning behavior.

Threats at schools happen somewhat regularly, but few rise to the level of a potential shooting. So the team will more often examine less serious, more transient reports, seeking to ward off problems before they escalate into something dangerous.

The framework for how teams respond will be laid out in operational training provided online

through the Ohio Peace Officer Training Academy.

“The program is built on best practices developed by Dr. Dewey Cornell, a clinical psychologist noted for his work on school violence, and the Secret Service — the experts at threat assessments, whether assassinations or school violence,” Porter said. “We built off systems proven to work.”

In a case involving a student, a team would look at what is going on in the teen’s life, the setting in which the threat was made and the choice of target.

“This isn’t just a criminal case,” Porter explained. “The main focus is the behavior. We want to identify this student’s issues from a 360-degree perspective and look for what triggered the behavior: Is it a death at home? Is it abuse? This is the legwork that will help you identify that.”

Once the team develops a full picture of the student’s circumstances, members will use a prescribed evaluation process to assess whether the student poses a risk. In situations that do pose a risk, the team will then:

- Develop intervention strategies to help the student and mitigate any risk.

- Follow up to make sure the help is working.

“This training will get the same best practices out to all communities across Ohio,” Yost said, “so that when schools need them, they have the tools to act.”

What the teams will not conduct is:

- Broad surveillance. Cases are brought to the team through the reporting of threats to Ohio’s Safer School Helpline (844-723-3764) or to teachers or other school officials.

- Profiling. The team examines a person’s behavior and mind-set at the time that he or she made a threat, not stereotypes or race, religion or other such characteristics. Behavioral assessments identify potentially violent situations and resolve them; they’re not intended to predict violence.

- Labeling students. The team’s purpose is to resolve the problem, not forever label a student as a troublemaker. Any records kept will be for follow-up purposes, to ensure the help is resolving the student’s problems.

In the second segment of the initiative, law enforcement officers who have taken the OPOTA training will join with a school leader and emergency management official to conduct vulnerability assessments of school buildings. These assessments underscore where a school has weaknesses, and they differ from emergency plans, which include an infrastructure map but focus on how to respond after a crisis has already begun.

“Doing risk and vulnerability assessments in a good way can be challenging,” Born said, “and it would be an expensive process for schools to handle on their own. That’s why a dedicated, funded program — taking advantage of the expertise of local law enforcement officers — makes sense.”

The initiative aims to ensure that all 5,200 of the state’s school buildings that host students undergo vulnerability assessments.

A 185-question form detailing the areas that should be evaluated will guide those conducting the assessments. The results will highlight any areas in need of strengthening.

The Attorney General’s Office is offering grants to fund those reinforcements — about $10 million to schools in each year of the two-year program.

“The state now is basically blind on where schools’ risks and vulnerabilities are,” Born said. “For example, someone says we should put up ballistic materials on the windows; we should put up video cameras; we should hire security guards. Yet when you do the walk-through on the risk and vulnerability assessment, you find out a few employees have duct-taped the back door open so they can go out and smoke.

“With these assessments, local school officials will get immediate guidance on safety gaps that need to be fixed,” Born said. “And Ohio’s going to get a complete picture of where our priorities should be, where we should spend money and what we should do to fix the problems.”

Law enforcement and assessment teams

The Attorney General’s Office expects to pay individual school resource officers to take the online OPOTA training. After that, an officer will be paid per school vulnerability assessment.

“Empowering local law enforcement with the opportunity to do that makes sense for two reasons,” Born said. “One, they’re in the schools, they know the schools, and they’re going to respond to an incident. And two, it gets back to local control with general statewide guidance.”

That said, program leaders recognize some people, including officers, might be sensitive to the idea of bringing law enforcement into school decisions.

That is why the Behavioral Assessment Teams will be led by a school leader and include other members of the school community, such as teachers and guidance counselors. The presence of an officer is beneficial, in part, because decisions about whether a matter should be referred to local law enforcement can be made more efficiently.

Also, not all school threats come from students. For example, the 20-year-old gunman who attacked Sandy Hook had no link to the elementary school.

The law gives police officers powers that it doesn’t give to school officials, and vice versa. Having members from both groups, then, lets the team cover a wider area without needing to find outside help, which can consume valuable time in a potentially dangerous situation.

“When does law enforcement get involved?” Born asked. “That is what this course tells you.”

A 20-page portion of the training details the framework for how to evaluate the seriousness of a threat. If the team determines it to be very serious and substantive, the law enforcement officer will act as the link between the team and his or her home agency. The local police or deputies will then investigate to determine whether the student or other person has started preparations for an attack, or committed other criminal acts.

“Look, every officer in Ohio has completed more than 700 hours of training to get certified,” Yost said. “And they specialize in addressing out-of-line behavior on a daily basis. For the times when a student is crossing into that area, having that expertise already on hand just makes sense.

“But, like everything in life, there has to be balance,” the attorney general continued. “These teams will work together on a regular basis, so they’ll find the balance that works for them. We’re laying out a framework, but flexibility and customization are essential. Every school is different; every situation is different.”

The plan is to have the training course available online in January; officers would have through June 30 to complete the course. Next, the officers will be asked to engage with school leaders to initiate the formation of a Behavioral Assessment Team, as laid out in House Bill 123.

Once the new fiscal year starts July 1, the school building vulnerability assessments could begin.

“This initiative sets forth a standardized, statewide framework to address prevention, intervention and training,” said Hartman, the school resource officer. “And it provides the much-needed funding to ensure all schools can benefit.”

The initiative stems from a promise Yost made in 2018 when he was running for attorney general.

“Local law enforcement and schools across Ohio have done the important work to get ready to save lives once a crisis begins,” Yost said.

“Now, what our state needs is the work that lets us stop the active aggressor the day before he gets to the school,” he said. “We want to stop him before he ever starts planning.

“We need to put just as much time and effort into preventing that.”

Assessment framework

One of the tasks for Behavioral Assessment Teams will be to set up an analytical approach to determine the seriousness of threats made by students or others. For a case involving a student, the suggested framework, based on recommendations from the Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center, would have the team consider:

- What are the student’s motivations or goals?

- Have there been communications suggesting the intent of the threat?

- Has the student shown an interest in something the team deems inappropriate? (An earlier task for the team involves defining prohibited and concerning behaviors.)

- Does the student have access to weapons?

- Have stressful events recently taken place in the student’s life?

- Does the student experience emotional or developmental issues?

- Is the student experiencing hopelessness or desperation?

- Does the student see threats or violence as a way to resolve problems?

- Are other people concerned about the student’s behavior?

- Does the student have the capacity to carry out a threat?

- Is there evidence of planning for an attack?

- Are the student’s actions consistent with his or her words?

- Does the student have positive or prosocial influences?

Threat determinations

The actions a Behavioral Assessment Team takes to help and/or discipline a student, and to protect other students and staff members, are guided by where the threat falls on this scale:

- Not a threat

- Not a threat, but an expression of humor, rhetoric, anger or frustration

- Transient threat that does not involve a real intent to harm anyone

- Serious substantive threat

- Very serious substantive threat